This webpage won't be updated anylonger.

Please visit: www.gerhardsengerner.com

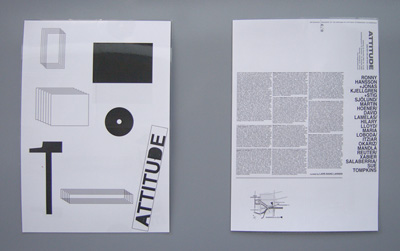

Xabier Salaberria

Poster, 2006, 42 x 59,4 cm

designed for the Attitude show

Xabier Salaberria

Poster, 2006, 42 x 59,4 cm

designed for the Attitude show

Martin Hoener

Installation view

Martin Hoener

Allee im Schneegestöber, 2005

Oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm

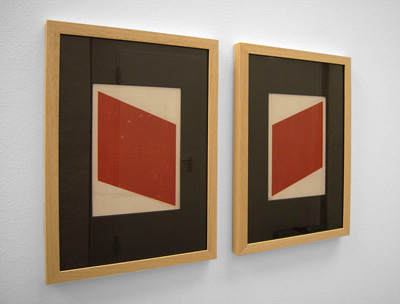

Martin Hoener

Hinten, 2004

Vorne, 2004

C-prints on photographic paper, 17 x 12 cm (30 x 21 cm framed)

No. 3 of ed. 5 + 1 AP

Martin Hoener

Unser Kopf ist rund, damit das Denken die Richtung wechseln kann,

2006

C-prints on photographic paper, 21 x 29,7 cm (30 x 30 cm framed)

No. 1 of ed. 9 + 1 AP

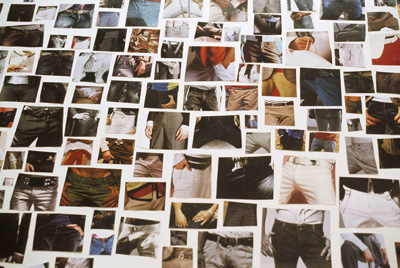

Hilary Lloyd

Untitled (Cut-Outs), 2006

80 Slides, Kodak EKTAPRO 9020 Slide Projector

Unicol Projector Stand, Variable Dimensions

Ed. of 3 + 1 AP

Hilary Lloyd

Untitled (Cut-Outs), 2006

80 Slides, Kodak EKTAPRO 9020 Slide Projector

Unicol Projector Stand, Variable Dimensions

Ed. of 3 + 1 AP

Installation view

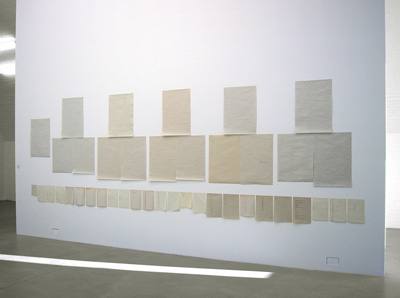

Sue Tompkins

Untitled, 2006

18 sheets of newsprint , 71,1 x 50,8 cm

Your side effect, 2006

36 sheets, variable paper, Variable dimensions

Detail:

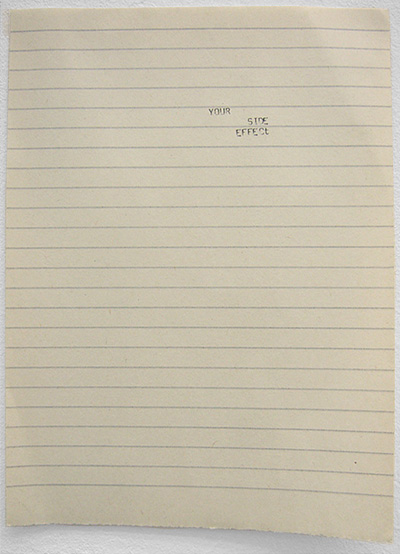

Sue Tompkins

Your side effect, 2006

36 sheets, variable paper, Variable dimensions

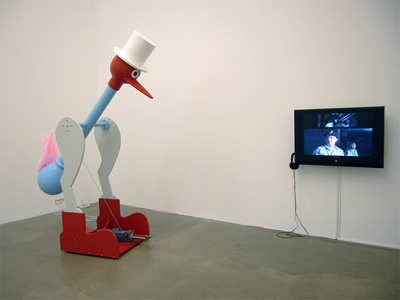

RIDE1: Stig Sjölund, Jonas Kjellgren, Ronny Hansson

Alien vs Ride1, 2006

75 x 75 x 250 cm, Plastic, wood, iron + DVD

(2 part installation), Ed. of 6

RIDE1: Stig Sjölund, Jonas Kjellgren, Ronny Hansson

Alien vs Ride1, 2006

75 x 75 x 250 cm , Plastic, wood, iron + DVD

(2 part installation), Ed. of 6

RIDE1: Stig Sjölund, Jonas Kjellgren, Ronny Hansson

Alien vs Ride1, 2006

75 x 75 x 250 cm, Plastic, wood, iron + DVD

(2 part installation), Ed. of 6

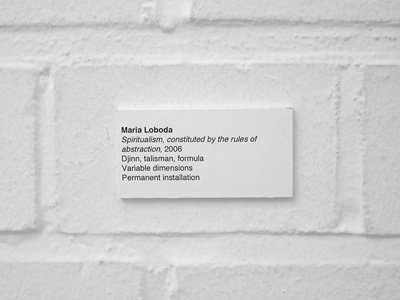

Maria Loboda

Spiritualism, constituted by the rules of abstraction, 2006

Djinn, talisman, formula

Variable dimensions, Permanent installation

Mandla Reuter

Untitled 1–5, 2006

(Photographs by Jeffrey Kocher, Los Angeles 2006)

61 x 50 each (67 cm x 56 cm framed)

Ed. of 3 + 1 AP

Mandla Reuter

310506 Cinestar Original, 2006

1 hour 46 minutes, Unique

Itziar Okariz

Peeing in public or private spaces, 2001–06

Video, 8 minutes, Ed. of 6 + 2 AP

Itziar Okariz

Peeing in Public and Private Spaces: c/o – Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin,

Nov 18

2006, Performance, Photograph by Xabier Salaberria

Itziar Okariz

Peeing in Public and Private Spaces: c/o – Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin,

Nov 18,

2006, After performance, Photograph by Xabier Salaberria

David Lamelas

Pared doblada, 1994

3 cardboard boxes each containing one sheet of folded paper

Dimensions of the boxes: 2 x (50 x 45,7 x 8,6 cm), 1 x (55,7 x 44,1 x 6,5

cm)

Dimensions of the paper sheets: 4 x (238 x 86) cm, Ed. 1

Pressrelease

DON’T GIVE ME THAT ATTITUDE Attitude is seeing how far you can go. It

is the characteristic and controlled manner in which you do the things you

do, or it can even be a kind of weapon. It is the way you pace and perform

your appearance, how your intentions are played out and resonate in other

people. It means defining the threshold of your personality, and how this

threshold is to be perceived by others. A good attitude defines space without

being territorial: it is a dynamic catalyst in social processes - a magnet

for the gaze, the site of a struggle and an exercise of freedom. Because it

is disruptive, you could say that attitude destabilises middle class ideology.

Whereas the middle class is oriented towards a normality that bypasses difference,

hence requiring no articulation, attitude is neither defensive nor conformist.

An attitude is the open negotiation of what or who society expects you to

be, in relation to your gender, body, ethnicity, class or subculture, education,

sexuality etc. As such, it is associated with style, but is by no means synonymous

with it. Unlike style, attitude isn’t only visual or aesthetic, it is

also determined by social intelligence and behaviour (pride, self-respect).

It goes beyond concepts that organise style, such as coherence and collective

ritual – in other words, style can be appropriated, attitude cannot

(if you appropriate an attitude you are a fake). In this sense, the function

of attitude is its subjective interpretation of the revolt of style. As a

friend of mine who was a punk in the 1970s lamented a few years ago: “Punk

doesn’t mean anything anymore. Today it only means that you are an aggressive

bum.” Good style is no guarantee for a good attitude.

The Attitude exhibition is not just about sassiness, or the appearance of

the self, but also examines how forms can become an attitude. Art with an

attitude confounds our expectations of the medium and location of the work’s

presentation, thereby conveying a strong performative dimension: it assures

a certain intimacy with the beholder, and emphasises - often in a gestural

way - the singularity of each piece vis-à-vis other art works. And,

to be sure, attitude is also an artistic strategy of how to relate to the

role of the artist.

THE ARTISTS In the installations, environments and designs of Xabier Salaberria

(1969, Donostia / San Sebastián), graphic and industrial forms become

formats for social interaction. Some of his works are made for specific functions

(such as the bar environment he created with Gorka Eizagirre for the Frankfurter

Kunstverein, 2006, quoting the spatial politics of the traditional Basque

tavern, the sidraria), while others take the simple and un-specific form of

big slabs of concrete that invites (rather than prescribes) collective activity

in public space (for example Plataforma de hormigon, Donostia / San Sebastián,

2002). The poster he designed for the exhibition suggests how attitude is

something that is not natural or given, but rather produced with and between

positive and negative, dynamic and static elements, in order to open up to

new possibilities. At the same time, the pictorial elements in the poster

seem to encourage intervention or resistance, clearing a space for something

unforeseeable or undetermined to take place.

The Stockholm-based collaborative Ronny Hansson, Jonas Kjellgren and Stig

Sjölund have worked together since 2004. With a humorous, anti-authoritarian

ethos, their works debunk morality and comfort, such as their amusement park

rides that confront the beholder with laconic dysfunction: the one-person

Ferris wheel that takes the beholder for an excruciatingly slow 360° ride,

or the conveyor belt that takes you into the air only to drop you on a mattress.

Anyone for interactive art? Their work for the Attitude show, Alien vs. Ride.1

(2006) consists of a 2,5m tall kinetic sculpture of a bird with a top hat

and orange boots. The bird tilts purposelessly back and forth and creates

a danger zone as its pointed beak descends from above. The bird responds to

a video in which the artists re-enact the first scene of the space horror

movie Alien. In this, a “dippy” or “happy bird” –

the little movable object that was a domestic design fad in the 1970s and

very common in homes as well as on office desks – appears inexplicably.

In Alien vs. Ride.1 a fascination with popular culture is laced with the desire

to challenge the art space’s rationality as well as the physical integrity

of the beholder.

Maria Loboda (Krakow, 1979) has cast a spell on the Attitude exhibition. Or

more precisely, she has bought a so-called Giant Formula from an Indian shaman

which she donated to c/o gallery. The formula includes a step-by-step prescription

for evoking the benevolent giant genie Saleemi. Whoever follows the formula

– in this case Atle Gerhardsen, on behalf of the gallery where Saleemi

will reside – will conquer Saleemi and its supernatural powers. The

powerful giant has a human shape and will be visible only to the person who

follows the formula. The shaman promises that it is in Saleemi’s powers

to (among other things) convert living organisms into stone, change coals

into treasures, impart the secret of invisibility, provide longevity up to

several hundred years, heal the sick, provide good fortune in lotteries, bring

back runaways, learn languages, procure love and give great honour in military

affairs. Saleemi has been acquired at the price of 150 US$ and is a permanent

installation in the gallery space at c/o – Atle Gerhardsen.

The work of Itziar Okariz (Donostia / San Sebastián, 1965) is based

on performances in which she challenges spatial and cultural limits. In her

video Mear en espacios públicos o privados / Peeing in Public or Private

Spaces (2002), the artist is seen urinating in public and private spaces in

New York: on a bridge, in a subway station, in a parking lot, in a hotel room.

The acts are performed standing up, with neither shame nor secrecy, and usually

in the daytime. The image of the artist urinating subverts visual and spatial

regimes that has historically segregated the female body and rendered it invisible.

But more than subverting gender constraints, the artist’s urinating

has the detached character of a ritual. This is territorial pissing as defiant

production of space, a rock’n roll posture: as the rock singer masters

the stage and “gives herself” to the audience in a gesture of

sincerity, Okariz also takes the space around her by literally giving something

of herself. As a private act turned inside out, peeing becomes a way of demonstrating

control over a situation – if only fleetingly. For the opening of Attitude,

Okariz will perform Peeing in Public or Private Spaces.

Mandla Reuter (Nqutu, 1974) shows two works in the exhibition. One is the

series of photographs Untitled 1–5 (2006) (photographs by Jeffrey Kocher)

that follows a sunset ad absurdum: between the first and the fifth picture,

the beautiful red and orange hues of a Los Angeles sunset fade into an indifferent

and uncommunicative black, as if it were the end of a Hollywood movie that

continued for a second too long, entering into a moment where the beholder

faces collapsed expectations of beauty and emotional intensity. Babylon (2005)

consists of a soundtrack of a blockbuster movie played back in the gallery.

Recorded during a screening in a movie theatre, the soundtrack is accompanied

by the audience’s coughs and crackling of sweets bags, thereby making

it a “polluted readymade”. By lifting the soundtrack a transport

of spaces is brought about: the illusory space of the movie industry is added

to the gallery, while the memory of a film is simultaneously conveyed and

withheld.

Attitude is often viewed quantitatively: it is noticed if you have a lot of

it. However, the work of Sue Tompkins (Leighton Buzzard, 1971) is pared down

and created with poor materials, and precisely by these means, it insistently

creates its own space and logic. Her installations and spoken word performances

revolve around the use of language: her minimally brief poems are poised on

pieces of paper – stationary, butcher’s wrapping paper, ruled

paper – and interspersed with coloured cardboard geometry. In the visual

silence around the poems, you begin to notice smallest of details –

the way they are typewritten, the creases in the paper. Their frail and exposed

position on the white expanses (or the way they are voiced in the silence

of a room) seems to make them prone to repetition and to significant typos

and neologisms, between which a colloquial tone meets structure and order.

Or the poems appear as something vaguely familiar, as if they were hit songs

from a parallel universe. Tompkins’ work spans a gap between the abstract

playfulness of conceptual art, and the emotional and associative fringes of

the information buzzing around our heads in the mass media galaxy.

Hilary Lloyd (Halifax, 1964) does not do portraits, but rather depicts the

poses and subtle acts that establish relations between strangers. As such,

her pictures of people have less to do with identity (who we “really”

are) than with the way we perform ourselves through ordinary acts. The subjects

in her work are people she has approached in clubs and bars, and their urban

anonymity is maintained: in a certain sense we see nothing more of them than

we would if we met them on the street. What we do see is what the writer Jan

Verwoert, á propos of Lloyd’s work, has called an “existential

glamour that defies easy categorisation”. For example, in Colin #2 (1999),

Lloyd asked a young man to take off a red tank-top and put it on again, as

slowly as possible – each time takes ten minutes, in self-imposed slow-motion.

Her work in Attitude is Untitled (Cut-Outs) (2006), projecting a slide series

of men’s crotches that are taken from fashion magazines. By focusing

on these sexualised poses, Lloyd satirises masculinity by the simplest of

means – repetition. In this sense, the work is a battle between attitudes:

the hysteric, phallic postures of the faceless men in the photos versus Lloyd’s

lingering, continuous focus.

Since the mid-1960s, David Lamelas (Buenos Aires, 1946) has developed an ephemeral

and peregrinating artistic project that focuses on the parameters of time

and space, which he has analysed in post-minimalist installations and performances,

as well as in photos and film. His work seems to be focused in part on creating

value-free conditions for recording time and for the observation of space.

Characteristic of this attitude, he said in an interview from 1972, “It

is impossible for me to make definitive statements. A piece is defined by

the person who looks at it.” Departing from conceptual and minimal art,

he is also fond of dramatisation as artistic strategy, as for example shown

in the Rock Star – Character Appropriation photos (1974), in which he

poses as Rock God on stage. He has also directed the professionally produced,

feature length film Desert People (1974). In Pared Dobleada (1994), Lamelas

revisits a recurring theme in his work, namely the modification of space.

The “doubled wall” is a kind of wallpaper made to cover the wall

on which it was originally shown as an artwork; or you could say it is a copy

of the wall that made it an art work in the first place. It is a gesture that

re-defines the frame of the white cube and the virtuality of the gallery space,

while also pointing back to the seminal exhibition When Attitudes Become Form

(1969), which helped shape the idea of processes in art within a minimalist

and conceptual aesthetic.

Martin Hoener (Wedel, 1976) works with multifarious styles and media as a

way to foster an open potentiality: his is a strategy of exploration by means

of simultaneous choices, in an attempt to transform restrictions into openings.

The photo Our Head is Round, Therefore We Can Change the Direction of Our

Thinking (2006) is a superposition of a photo of the night sky of southern

hemisphere on a photo of the night sky of the northern hemisphere. As a cosmic

image that connects and interweaves opposites, Our Head is Round becomes a

kind of allegory on the nature of art as it speculates on the possibility

to connect duality and difference in one, and the ability to look in several

directions at the same time… Allee im Schneegestöber (2005) is

Hoener’s version of Edvard Munch’s Avenue in Snow (1906). Ostensibly

made with the ambition to redo the painting better than Munch, Hoener has

turned the great Norwegian modernist’s clear and frosty vista into a

depopulated and almost psychedelic, purple and brown surface. What at first

comes across as pure attitude is, on second thought, a sincere homage rather

than an artistic parricide. Hinten and Vorne (2005) are graphic renditions

of the back and front cover of a Merve Verlag edition of Brian O’Doherty’s

classic text Inside the White Cube (1976). This book about the ideology of

the gallery space has been reduced to two hard-edged geometrical shapes, and

with its title and author removed, the critical excavation of the white cube

becomes two red eyes staring angrily back at the beholder.

Lars Bang Larsen